How I missed the execution

The jury is still out on whether divine intervention somehow draped an invisible bandanna across my face so that I could witness a shift in the landscape, or whether it was just an embarrassing blunder on my part.

Whatever the verdict turns out to be, the evidence shows I was a willing, some might say callously eager, grabber of an assignment handed me few weeks ago to witness the execution last week of Darryl Barwick, of Jacksonville, his residence as listed among the six children, 10 grandchildren, and four great-grandchildren in the obituary published 14 years ago for his mother, a lifelong resident of Panama City.

This detail as to where Barwick resided was not the most precise, since as far back as 1992 he had been on Death Row destined for the execution chamber at Florida State Prison, which is in Raiford, not Jacksonville.

On Wednesday at 6 p.m., he was the latest of about 300 people, all but three of them men, awaiting the walk to their death.

Unfamiliar with the details of the case, as it was in Bay County in April 1986, when I was 37 years younger than I am now and living in Ohio, I read up on the murder for which Barwick’s life would now be taken by a “procedure…compatible with evolving standards of decency that mark the progress of a maturing society, the concepts of the dignity of man, and advances in science, research, pharmacology and technology,” according to a March 10 letter to Gov. Ron DeSantis from Florida Department of Corrections Secretary Ricky Dixon.

“The foremost objective of the lethal injection process is a humane and dignified death,” he wrote, stressing no steps would allow for the “unnecessary or wanton infliction of pain and suffering,” and that the entire process would be transparent, and that “the concerns and emotions of all those involved” would be addressed.

The need for that transparency is the reason that I was, as a member of a handful of media representatives, enabled to witness the last minutes of Barwick’s life.

*

The woman who stood in front of me at the McDonald’s I pulled into in Lake Butler on my way down was complaining about not getting her ice cream cone. She gave me directions to Raiford, and I then told her I was a reporter on his way to an execution.

“Oh, there’s one today?” she said. “I don’t follow them any more, there’s so many.”

Actually, this is the third execution scheduled in Florida this year after a hiatus dating to 2019.

She ticked off a list of her relatives who work somewhere at the massive multi-prison complex and then, as she began eating her cone, told me her son was in prison for 10 years.

“You know why?” she asked, relaxedly.

I knew to represent my profession honorably it was important to venture a plausible guess, so I deliberated carefully.

“Drugs?”

She nodded. “He duct taped his girlfriend to the steering wheel of her car and ran off with their child,” I think she said to Louisiana, I can’t recall. “Then he stole a cop’s motorcycle.”

I thought maybe that was a humane way to prevent her from running off with their kid, but said only “why did he steal a cop’s motorcycle?”

“He’s mean,” she replied, with emphasis. “He’s a Halloween baby.”

She was gone when I left, after reviewing over my burger a text from a colleague that advised Barwick would be accompanied to his execution by Father Dustin Feddon. “I have personally experienced Darryl as a man of profound compassion, mindfulness, faithful in prayer, and in service to his fellow brothers on the row,” wrote the priest.

Barwick had been absent compassion, when at age 16 in Panama City, he raped a 21-year-old at knifepoint in 1983, served two years, returned to the same residence in Panama where he had been living, and three months later, at age 19, stabbed a 24-year-old neighbor, who he had eyed while she was out sunbathing, 37 times as she fought back against being raped. Her sister, who lived with her, had come home to find Rebecca Wendt dead, and it took police about two weeks to get all the evidence they needed to arrest Barwick.

The Wendts did not attend the execution, and based on the talk among the gaggle of reporters gathered in a field in front of the prison employment office for the briefing, they have stayed completely clear of public comment.

*

Why had it been 37 years since justice was handed down for killing Wendt, a crime to which Barwick confessed and for which an extremely infinitesimal amount of doubt as to the culprit existed?

Following his conviction, a jury voted 9-3 that he should get the death penalty, and the judge later made clear in his decision that Barwick’s act had met all the necessary stipulations as to atrocity, heinousness and cruelty, and was not mitigated by evidence that Barwick had been mistreated by his father as a child.

Barwick’s lawyers were able to get his original conviction overturned, arguing successfully that the prosecutors had consistently dismissed those potential jurors who were Black. On his second trial, the verdict was unanimous for the death penalty.

I spoke with two criminal defense attorneys in my research, Ethan Way, who practices here, and a man who he called “the best death penalty lawyer I have ever come across anywhere, anytime, anyhow,” Walter Smith, who used to be the public defender here in the 1980s and then went to Bay County, where he handled scores of first degree murder cases before retiring at the end of 2015.

Smith said that even though both the victim and the killer were white, evidence suggests Black jurors are less likely to vote for capital punishment and thus prosecutors lean towards their dismissal.

Both men said the overwhelming majority of capital cases are handled by government attorneys, since private counsel would be way too expensive for those on trial, and could bankrupt a county if it went on too long.

Smith said the state has put in place certification requirements for the lawyers taking these cases, and there has to be at least two, so there is an assumption of basic competency, and so as not to lead to, as Smith recalled, an instance where a judge appoints a probate attorney to do a death penalty case.

“There is no such thing as an automatic depth penalty,” he said. “Most (murder cases) turn on the facts. You have to be realistic about it.”

Smith’s approach, if he can not secure a conviction on a lesser charge, is to establish the truthfulness of his case, so that when it comes time for the penalty phase, the jury is more inclined to believe the sincerity of his appeal for mercy.

“It’s not for the weak of heart and certainly not for inexperienced attorneys. That’s a recipe for disaster,” he said. “And it’s totally random. The better the lawyer, the better your chance of getting the life sentence.

“I’ve had people who committed horrible crimes that got a manslaughter conviction. It doesn’t deter anybody and it doesn’t send a message to anybody,” Smith said. “It’s just been a dismal failure. I have innocent people sitting in prison today because of the death penalty.”

Smith said because the process can take so long, the families of both the victim and the condemned often lose faith in the system.

“They start going down rabbit trails. There really is no closure for either side,” he said. “I’ve had families call me and ask ‘what’s going on? They start doubting the system themselves, when there’s more to it than what they’ve been told.”

While Way doesn’t believe in a complete ban on capital punishment, he thinks child rape and murder might call for it, the state’s current move to no longer require a unanimous verdict is unconstitutional, in his eyes.

With lengthy appeals, and the need to bring in large numbers of mental health experts and mitigation specialists, Way said capital punishment is both expensive and ineffective.

“I have never come across, in my 25 years of criminal defense work, anyone who thought it (capital punishment) was a deterrent,” said Way. “10-20-life is an effective deterrent. But most people who commit first degree murder aren’t worried about the penalty.”

“I have met exonerees, and we’re not talking about legal sleight of hand,” he said. “Death is different, you got the government running the show, from the people who brought you the Challenger disaster. Things blow up.

“It costs too much money,” Way said. “I understand the revenge business, I understand eye for an eye. But the death penalty as currently practiced is ineffective; those who die are old men.

According to an information sheet passed out at the first media briefing, at 3:30 p.m. Wednesday, the average length of stay on Death Row is a little more than 16 years, with 46 the average age at time of execution, and 29 years old the average at offense for executed inmates.

At the same briefing, Kayla McLaughlin Smith, director of communications for the Florida Department of Corrections, told reporters Barwick had been woken up at 4:15 a.m.; and at 9:15 a.m. ate his last meal, of fried chicken, macaroni and cheese, black eyed peas and rice, corn bread, ice cream and a cola, the entire meal required to cost no more than $40 and to be purchased locally.

He had met with his spiritual advisor. None of his family members were allowed to attend. The reporters who witnessed the execution said they were not sure who each of the people in the witness room were.

Barwick didn’t meet in person with family members, but had spoken with them by phone in recent days, prison officials said.

*

As I turned down the road towards the prison, I went through a place called Varnes Branch, which seemed like little more than a stand of trees and some pasture. I thought, isn’t that the surname of the Apalachicola chief of police, and of a former Franklin County sheriff?

Then a little ways down that same road, County Road 121, was Sapp Cemetery, and then it occurred to me, a little more ominously, that every week I am emailed the arrest report from the sheriff’s office by a young woman with that last name.

If ever there was a reminder of the spirit of the lawman, a spirit that drifted across North Florida as far west as Franklin, it was in these named places. What would be happening this afternoon would be in keeping with the legacy of the law-abiding people of these parts, would it not? People we know and love and count on to keep us all safe from harm.

*

Following the first media briefing, I drove into Raiford, where a cheerful cashier named Alexie allowed me to charge my iPhone behind the counter, with a new cord that she was happy to let me use.

I asked her about the death penalty, and it didn’t appear to be a matter that vexed her often. “I guess there has to be consequences for your actions,” she said.

I made sure to be back in time for the 5 p.m. departure of the van that would take a handful of us across the road to where the execution would be taking place.

As we were beckoned to saddle up and head out, I was reminded that I would have to leave my wallet and cellphone locked in my car, and take with me only my identification and five one-dollar bills, for use in the vending machines if necessary.

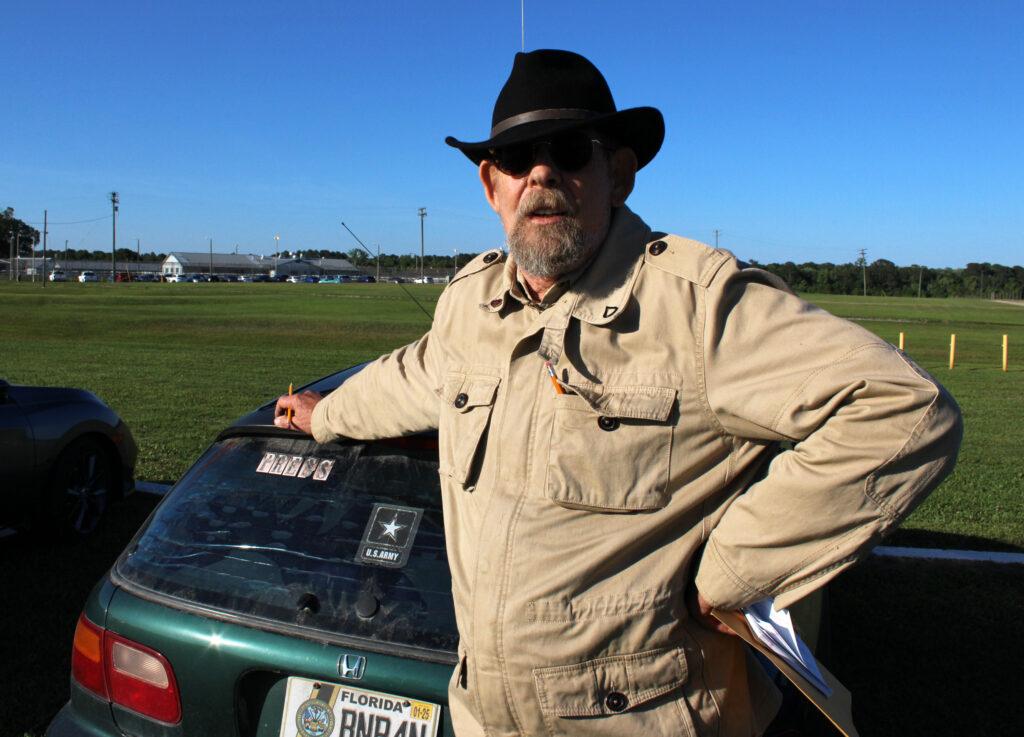

I was last to step into the van, and once in, heard from the senior reporter present that since we would only be allowed a state-issued notepad and two pencils, it was important we pool our notes afterwards to ensure we captured as best we could Barwick’s last words.

Being that John Koch has witnessed 83 executions, dating back to Ted Bundy’s death in the electric chair in January 1989, his advice was accepted as press corps dogma.

As we stepped off the van, and approached the barbed wire entrance, I felt my stride slowing, as if a crosscurrent was challenging what for a few weeks had been my palpable curiosity, bordering on thrill-seeking. Some said I was brave to be willing to witness it, others that my tone was irreverent and disrespectful.

Just before I reached the entrance, I heard the staccato ring of an arriving text message, from the phone in my pocket. I was startled and knew instantly it would be a problem. I tried to make my case, that it indeed had been inadvertent, and could someone hold it for me, or let me leave it outside, or inside the van? One of the communications people asked the assistant warden and he denied my appeal. A prison guard was directed to take me back to the media briefing site and was told I would be welcome to attend the post-execution briefing. I had broken a rule and this was the consequence.

Once back across the road, my chagrin was about to worm its way into despair, when for some reason I lifted my head up and saw that unlike what had been the situation when the witness van had left, the field next to the parking lot was now filled with a crowd of people.

*

Looking for something better to do than skulk, I walked over, and saw that on that hill were seated a gathering of death penalty opponents. Their non-witness of the execution, and strenuous opposition to it, would instead be the resolution of the evening’s story.

A group of middle school students from Our Lady of Lourdes Academy in Daytona Beach had taken a bus up to be on hand for the protest. Their parish priest, Father Phil Egitto, has an active social justice outreach, and he led the ceremonial protest that would soon take place.

“We respect life, from conception to mortal death,” said Melanie Wilson, the students’ teacher. “It’s not about the person being executed. It’s about the sanctity of life.”

Maria DeLiberato, executive director of Floridians for Alternatives to the Death Penalty, was on hand, and spoke briefly, later fulfilling a promise to text me the group’s press release after the execution.

“Tonight, by killing Darryl Barwick, we the People of the State of Florida also killed the belief that redemption matters. That remorse matters. That people, especially those who are sentenced to die as teenagers, are capable of change,” it read. “This execution cements the short-sighted notion that people are irrevocably defined by the worst thing they have ever done.”

The statement goes on to say that while Barwick had a brutal and abusive childhood, the story of his life shifted after he was imprisoned for the murder.

“Though it was still prison, he was not subjected to constant physical violence at the hands of those supposed to protect him. He developed relationships,” it read. “He’s had a pen pal, a Sister of Mercy and a professor emeritus at a university, for nearly 30 years. His spiritual advisor has visited him regularly over the years and brought him peace and comfort in their shared Catholic faith. He wasn’t a disciplinary problem. His neighbor on death row was legally blind, and Darryl helped him navigate everything.”

During a time in the ceremony, when there were readings from Isaiah and Luke, I walked over to a small area, on the other side of a group of Florida Highway Patrol offices, which was labeled “supporters.” There stood just two people, a man and a woman, who politely declined to identify themselves or pose for a picture, but shared that they lived not far away and had no involvement with the Wendt family.

They too said they had come down out of a “religious concern,” out of their Christian faith, to do what the Bible says, as found in the book of Numbers.

“I feel there are consequences for actions,” said the man. “And no one is above consequences.”

At 6 p.m., at the same time that Barwick was administered an etomdiate injection to sedate him, and then shots of rocuronium bromide and potassium acetate to bring on his death, the gathering of opponents conducted a ceremony in which a long queue of participants each walked up to an enormous bell and clanged it loudly with a mallet, most all of them declaring “Not in my name!”

The priest led them in a prayer for compassion and mercy for a lengthy list of persons, for Wendt and her family, for all the Death Row inmates and for the correctional officers, and for Barwick and his family.

“May God our Father welcome him with mercy and love to the kingdom of heaven,” said Father Phil.

Koch, after he returned from the execution, shared his notes with me of a portion of Barwick’s last words.

“It’s time to apologize to the victim’s family and to my family,” he said. “I can’t explain why I did what I did, but I’m sorry.

“And another thing I would like to say, the state of Florida needs to show some kind of compassion and kindness for each other with so many kids in prison, there are 14- and 15-year-olds serving life sentences.”

As the service came to a close, and I walked back to hear Smith report that Barwick had been declared dead at 6:14 p.m., Father Phil told the gathering that he had heard birds starting to chirp.

“Tonight, our Lord sends us a sign that Darryl has been called home,” he said.

Someone spared you a sight that would have stayed with you in pre-dawn darkness for the rest of your life. You should buy a gift for the person who called you.