Wanna play cowboy?

When I was 12 or so…

Seems like most movie and TV cowboys have issues nowadays. They abuse their families (think 2021’s “Power of the Dog”); murder unforgivingly (as in Eastwood’s 1992 film “Unforgiven”); or end up being crazed androids (in “Westworld,” the franchise begun in 1973, now an HBO series).

Things were different when I was a kid. There were good guys and bad guys and we had no trouble telling which was which. Once we got our first TV, a black-and-white set with a 10-inch screen, we tuned into every Western we could find.

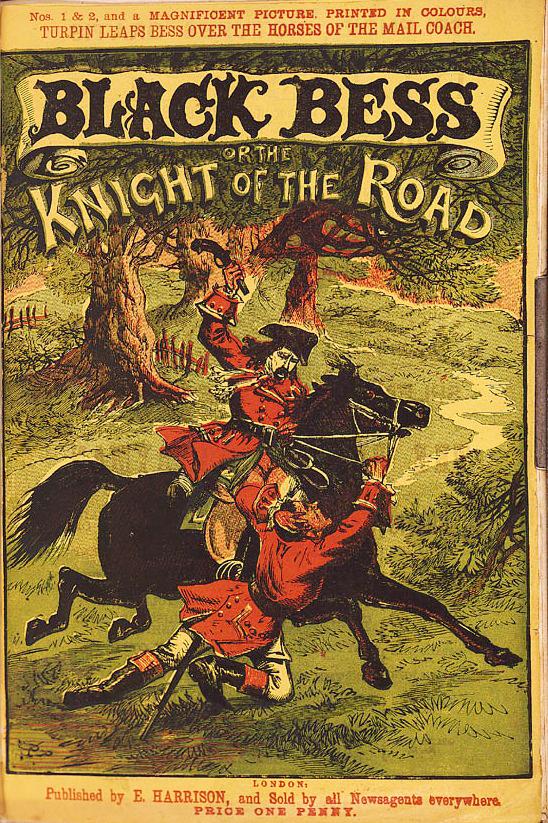

Stories of the Old West had become increasingly popular in the 19th century, with local legends adapted into cheap “penny dreadful” magazines, “dime westerns” (featuring characters like Davy Crockett, Daniel Boone, Kit Carson, and Buffalo Bill), and the hundreds of pulps published from the 1890s into the 1950s.

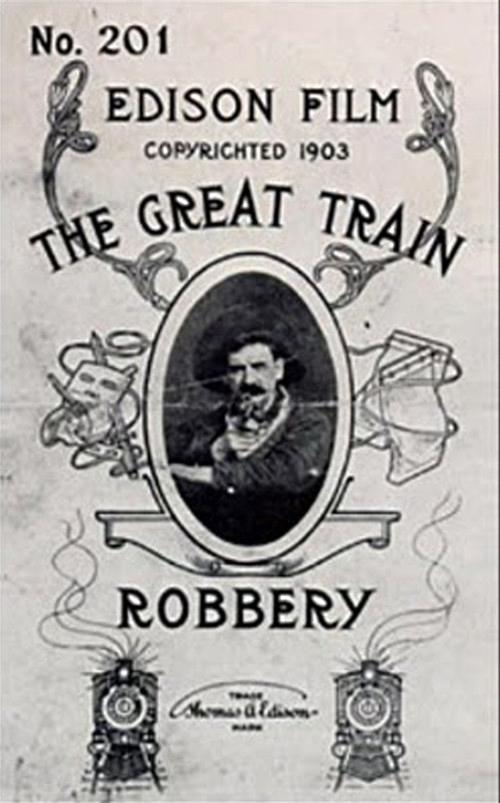

With the advent of motion pictures, the first cowboy movie produced in the U.S. was “The Great Train Robbery,” a 12-minute silent film created in 1903 by Edwin S. Porter. The villainous robbers were heroically foiled by a posse of locals. Lots more silents followed, and one of the first Western “talkies” from a major studio was director John Ford’s “Stagecoach” (1939), starring Claire Trevor and John Wayne in his first important movie role.

Before our family could afford a TV, we listened to Westerns on the radio. The first to hit the airwaves was the immensely popular “Death Valley Days,” which was broadcast 1930-51 and later moved to television, as did other radio favorites like “Gunsmoke” (on TV 1952-61), “Gene Autry’s Melody Ranch” (1940-56), and “The Roy Rogers Show” (1944-55).

As more and more Americans bought television sets, Westerns became one of the medium’s most popular genres during the ‘50s and early 60s. In 1959 there were 30 different cowboy shows airing weekly on the three major networks, ABC, CBS, and NBC – inspiring the Olympics’ doo-wop hit, “Western Movies” (1958).

An early favorite of mine was Hopalong Cassidy, a fictional cowpoke created in 1904 by Clarence Mulford and popularized in a series of short stories and novels. The character’s name came from his hopping limp, the result of a leg wound in a gunfight. William Boyd played “Hoppy” in the movies (1935-48) and on radio (1948-52), and then on NBC (1949-52), the first Western television series. Boyd was a brilliant entrepreneur and earned millions marketing all kinds of merch with the Hopalong name and image, including the first TV-themed Aladdin lunchbox. Pretty sure I had one!

“The Gene Autry Show” aired on CBS from 1950-56, the first four seasons in black-and-white, the last in color. Autry, owner of the L.A. Angels baseball team from 1961-97, was the “singing cowboy.” His renditions of “Here Comes Santa Claus” and “Rudolf the Red-Nosed Reindeer” brightened my Christmases.

Roy Rogers and his real-life (third) wife Dale Evans teamed up for NBC’s highly successful “Roy Rogers Show,” 1951-57. The ever smiley cowboy/cowgirl couple – their horses were Trigger and Buttermilk – gave me the terrible joke I’ll tell at the drop of a Stetson, with the punchline, “Pardon me, Roy: is that the cat that chewed your new shoes?”

A couple more ‘50s TV cowpokes were, in a way, progressives. The Lone Ranger, played on TV by Clayton Moore, had a Native American sidekick and friend, Tonto (Jay Silverheels, a Mohawk from Ontario, Canada). The characters were conceived in 1933 for a Detroit radio show and performed to listening audiences of up to 20 million (me among them); the TV show aired on ABC from 1949-57. The show’s writer, Fran Striker, penned this as her hero’s moral code: “I believe that to have a friend, a man must be one. That all men are created equal and that everyone has within himself the power to make this a better world.”

There were two Republic Pictures Lone Ranger serials in 1938-39, Dell began a comic book series in 1948, and the television show started the next year, sadly ending in 1957, when I was 12 or so. The 2013 Disney film, an origin story, starred Armie Hammer in the title role and, to the chagrin of some Native Americans, Johnny Depp as Tonto. Depp’s performance won him the Golden Raspberry Worst Actor award.

Like the Lone Ranger, who avoided using his guns and would never shoot to kill, Lash (Alfred) LaRue was ahead of his time in opposing gun violence. He never carried a pistol but took down the bad guys with his trusty 18-foot bullwhip (something for police to consider?).

He always wore black (like Hopalong) and influenced my choice of that as my favorite color; for a long while I even wanted to change my name to “Lash,” which sounded so much cooler to me than “Richard.” Besides numerous other film and television roles, LaRue appeared in a series of 11 “Lash” movies between 1948 and 1951, and the Lash LaRue comics I so loved were published from 1949-61.

All those cowboy shows and comic books inspired our outdoor games. I’d walk up the road, Harold Street, to Greg Lachowicz’s house, or he to mine, and we’d ask, Wanna play cowboy? We’d strap on our six-shooters, loaded with rolls of caps, and don a black Lone Ranger mask if we had one left from Halloween. Or we’d cut long skinny branches from the weeping willow in Doc Forshaw’s yard for a whip, and play Lash Larue.

If Janey Servonsky was around, from two doors down, or Doc’s sister Edna Mae, they’d be the damsels we rescued; or sometimes they’d rescue us. And if we needed a posse, Greg had four younger brothers – John, Paul, Mark, and Blaise (they were Catholic). It was fun, and it all seemed harmless, in those days when the yard went on forever.

I never forgot the song, written by Dale and my sign-off here, that she and Roy crooned at the end of every show. Janis Joplin did an informal recording of the tune for John Lennon’s birthday three days before her death in 1970, and Van Halen covered it for the 1982 album, “Diver Down:” “Happy trails to you, Until we meet again. Happy trails to you, Keep smiling until then.”

Rick LaFleur, who was “12 or so” in the 1950s, is retired from 40 years of teaching Classics at the University of Georgia; his latest books are “The Secret Lives of Words,” a collection of his widely distributed newspaper columns, and “Ubi Fera Sunt,” a lively translation into classical Latin of Maurice Sendak’s children’s classic, “Where the Wild Things Are.” He and wife Alice live part of the year in Apalachicola, under the careful watch of their French bulldog Ipsa.

Meet the Editor

David Adlerstein, The Apalachicola Times’ digital editor, started with the news outlet in January 2002 as a reporter.

Prior to then, David Adlerstein began as a newspaperman with a small Boston weekly, after graduating magna cum laude from Brandeis University in Waltham, Massachusetts. He later edited the weekly Bellville Times, and as business reporter for the daily Marion Star, both not far from his hometown of Columbus, Ohio.

In 1995, he moved to South Florida, and worked as a business reporter and editor of Medical Business newspaper. In Jan. 2002, he began with the Apalachicola Times, first as reporter and later as editor, and in Oct. 2020, also began editing the Port St. Joe Star.