Chasing Shadows: How a Sicilian family shaped Apalachicola

By Pam Richardson Guest Columnist

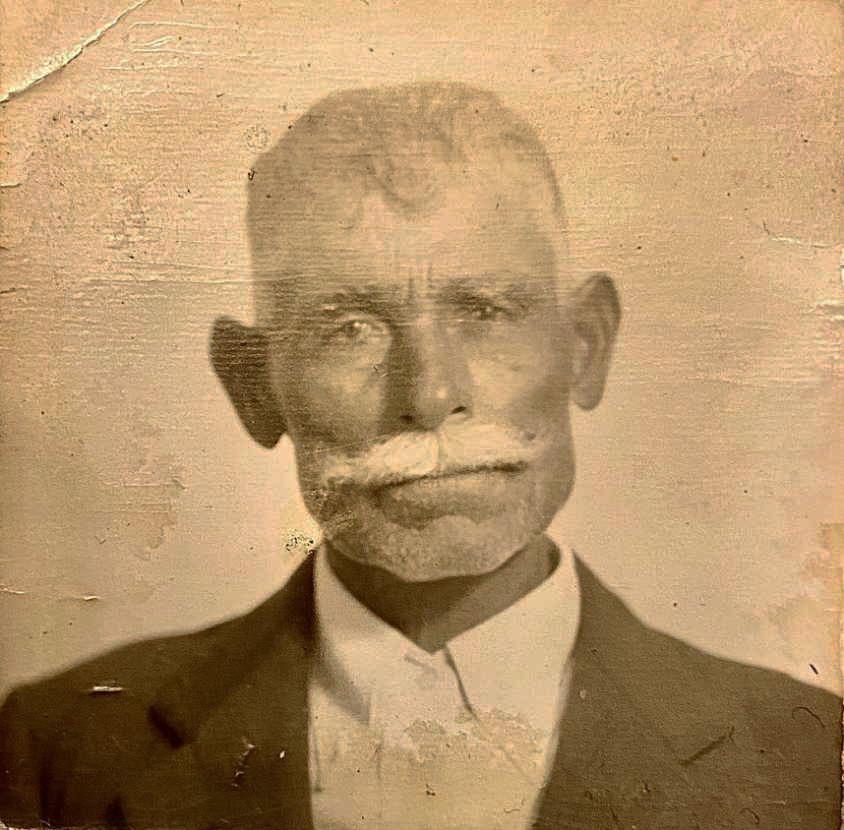

This old sepia-toned photograph of an elderly man has been tacked to the bulletin board above my desk for weeks. It is inexplicably compelling and moving. The chiseled set of the man’s jaw conveys courage and perseverance, the straight line of his mouth suggests an ability to withstand hardship, and the furrow between his brows speaks of worry or apprehension. But it is his direct gaze at the camera that is most arresting. This man has a story and I want to hear it. I wish that I could somehow travel back through time and ask him to tell it to me. Instead, I must make do with whatever traces of him I may be able to uncover.

He was born Mariano Licciardello about 1872 in the small town of Acireale on the east coast of Sicily and there, in his late 20s, he married a young woman named Ograzia Pellegrino. Life was not easy for Sicilians in those days; dire poverty, social unrest, exploitation of workers, and organized crime were rampant. This may explain why Licciardello made the radical decision, less than six weeks after the birth of his first child in November 1899, to leave his family in Acireale in search of greater opportunity in the United States.

Ellis Island records document Licciardello’s arrival in New York on Thursday, Jan. 25, 1900 aboard the SS Tartar Prince, a ship built to accommodate a thousand third-class passengers. He was listed as a married 28-year-old laborer, able to read and write, in possession of $20. It was also noted that he was not a polygamist, had never been in jail, and was in good mental and physical health. He gave his final destination as Apalachicola, with an uncle whose name on the immigration records is ink-smudged after the first three letters G-e-r. One can only imagine Licciardello’s bewilderment, not to mention enterprise, at having to get himself from New York to Apalachicola with no English and only $20 to his name! And, remember, there was no railroad service to this remote Panhandle town until seven years later.

It didn’t take long for Licciardello to see that he could make a good go of it as a fisherman here, so he sent word – and, no doubt, money – back to Acireale requesting that Ograzia and their son, Salvatore, join him. Mother and child immigrated in 1901, and all three were naturalized in 1905.

Licciardello does not appear on the 1910 census, but he is pictured in a photograph of the “Italian Hunt Club” taken about that time; he is the one on the left touting a Long Tom shotgun. Despina George, an Apalachicola native, believes the group’s name to be a modern invention. “It looks more like a drinking and lying club to me,” she jokes.

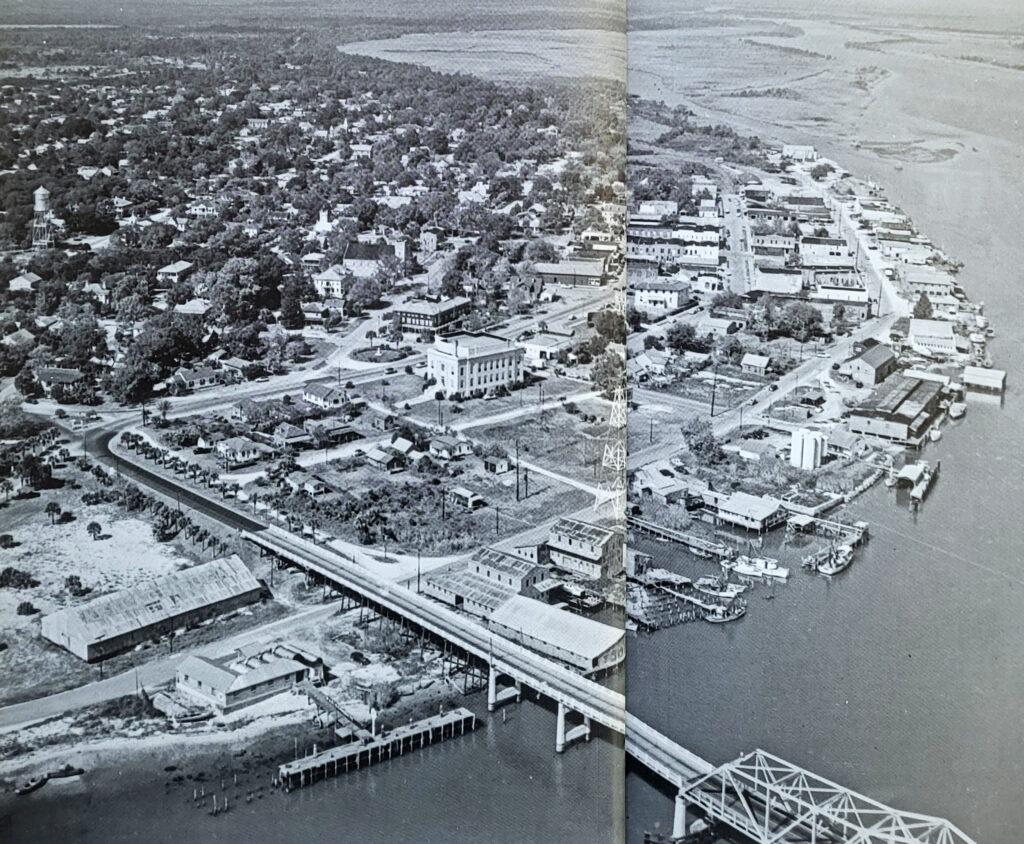

In 1917, Licciardello bought a house and two lots at 22 Commerce Street, where the Franklin County courthouse annex now stands. This neighborhood was known as Irish Town because its residents had been predominantly Irish, but even after the flood of Greek and Italian families replaced the Irish, the neighborhood retained its old name. Names that did change, however, were Licciardello and Ograzia, which were anglicized to Lichardello and Grace.

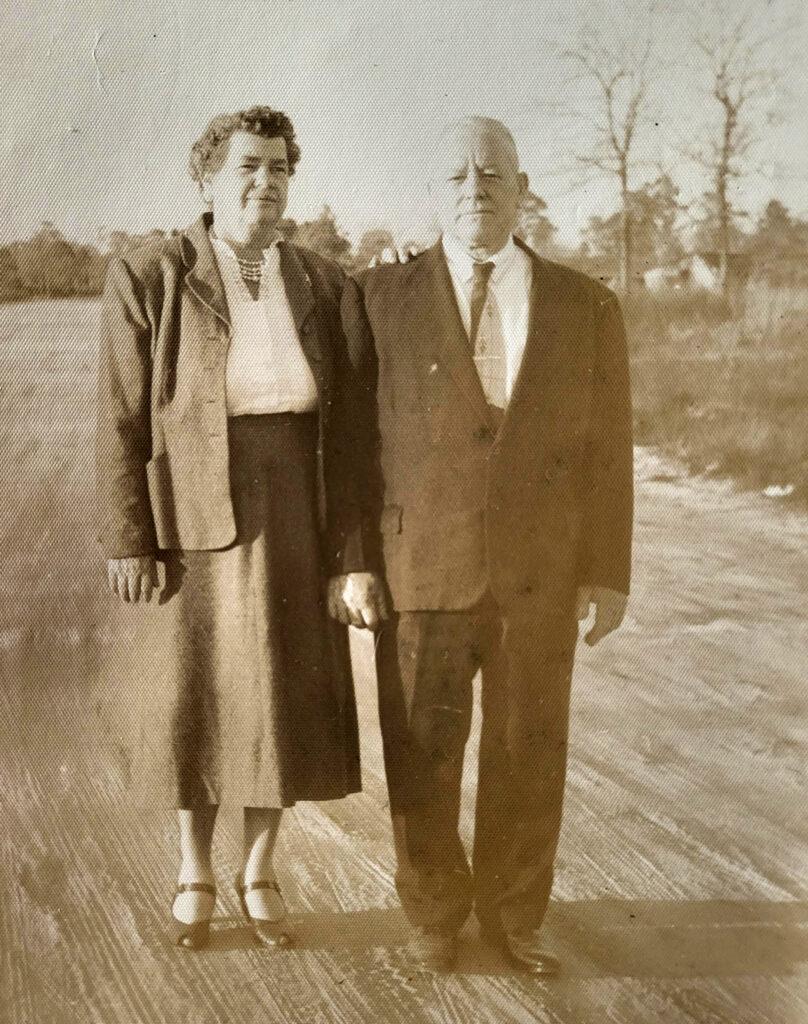

Lichardello bought his property from fellow Sicilian Angelo Spano, from the island of Lipari, who moved to Columbus after his wife got malaria in Apalachicola. Mariano and Grace raised their four sons and four daughters in the Commerce Street house. Despite having so many mouths to feed, Lichardello did well. We know he was able to purchase not only more lots in Irish Town, but also a 28-foot sailing vessel, the Josephine, built in Biloxi, on which he fished for red snapper and shrimp. On the 1920, 1930 and 1940 censuses, he gave his occupation as either oysterman or fisherman, working sometimes for a seafood plant and sometimes for himself.

The last Lichardello child, Mariano, or Geno as he was called, was born in 1918. All the boys followed in their father’s sea-faring footsteps and all did well. But on August 1, 1937, second son Alfio was fatally injured on the newly-built Gorrie Bridge when the truck in which he was riding collided with a sedan. The truck was completely demolished. Mariano purchased a couple of plots at Magnolia Cemetery on Bluff Road and buried his 34-year-old son there. In 1942, Mariano fell sick, and lingered for about a year before passing away. Grace, 10 years his junior, lived until July 4, 1947.

By a stroke of luck, I was able to locate both Alfio’s and Grace’s graves. Their stones, lying flat on the ground, were covered with years’ worth of dirt and tree debris, but once cleared, their names were plainly visible. Alfio’s stone, made of concrete, says simply: “Alfred Lichardello, December 7, 1903 – August 1, 1937” followed by the phrase “From mother’s arms into the arms of Jesus.” Grace’s stone is much larger and pure white; the words etched into it read “Ograzia Pellegrino Lichardello, born November 9, 1881, Sicily, died July 4, 1947, Apalachicola – Faithful, kind and true.” At its foot is one word: “Mama.” Within the plot enclosure is a third big, flat stone, also covered with soil and weeds, but it was found to have nothing written on it – no name, no date, no words. Is this Mariano’s grave? We may never know.

This hard-working fisherman left as his legacy more hard-working fishermen – daughters, too, but their stories are beyond the scope of this one. The oldest son was Salvatore, the only one of Mariano’s children to have been born in Sicily. His 1918 draft registration card, on which his name is spelled in the old, Italian way, describes him as short, of medium build, with brown eyes and brown hair and working as a fisherman for the Acme Packing Company in Apalachicola. Two years later, he married Frances Sarah Bailey of Sneads, and their daughter, Frances Dorothy, was born in 1925. For a time, Salvatore and Frances rented #23 Commerce Street, but they eventually moved behind his parents’ house to the corner of Forbes and Market streets.

A 1957 issue of the Apalachicola Times features a photograph of Salvatore’s boat, the “Dottie.” It is said this boat was originally named the “Mussolini,” but when Salvatore found a can of paint on the dock accompanied by a note which read “Change the name of your boat or we’ll burn it down!” he quickly obliged.

Most of the stories that have survived in the Lichardello family about Salvatore center around Frances who is said to have been tough as nails. Consider this: when Frances picked her husband up at the docks after a long day of fishing, she made him ride home in the trunk of the car because he smelled so bad! And this: when the state was planning to reconfigure the Gorrie Bridge, it repeatedly sent men to offer Frances money to either buy or move her house which was right in the way of the new bridge, but she resolutely refused. Each time “those damn bridge builders” came to her door, she greeted them with a shotgun. When Frances went to a nursing home in the 80s, she sold her house to a cousin who had it moved to 15th Street – and the new entrance to the city was finally accomplished.

Salvatore and Frances’s daughter, Dot, grew up and worked behind the counter at Buzzett’s Drug Store during the war years. One day a man stationed at the Army base (now the airport) strode into the store and caught Dot’s eye. She pointed him out to a co-worker and said “I’m going to marry that man!” He was Royce Rolstad from Wisconsin and, sure enough, several days later, he returned to Buzzett’s, and asked Dot out to a movie at the Dixie Theater. They did marry and had two daughters and a son, all of whom had children of their own. The names of these great-great-grandchildren of Mariano Lichardello – Krista Miller, Brian Miller, Kevin Pittman, and Royce Rolstad III – may be familiar to readers as they were all born and raised here.

When Mariano Licciardello decided to leave his homeland, he was one of the first of one million Sicilians (and three million Italians) who came to the United States between 1900 and 1914. In that context, his decision to immigrate may seem insignificant, but in terms of his own life, the lives of his wife and child, and his future bloodline, it was momentous. He took a giant leap outside the box and, through effort and determination, succeeded. It is no wonder, then, that his face, as seen in the photo of him as an old man, is so deeply etched with all that his risk required.

Pam Richardson is the vice-president of the Apalachicola Area Historical Society. She is indebted to Royce Rolstad III, Valerie Miller, Bobby Miller, and Krista Miller for their contributions to this story.

Thanks Pam for this informative article. My father’s family is from Sicily.

What a lovely story!

Thanks!

Interesting history . Thanks Pam

And I bet he had quite a story as well!