The Secret Lives of Words: Florida’s flamboyant flamingos

If you’re a senior citizen like me (there’re plenty in Apalach), you may recall “When the Swallows Come Back to Capistrano,” the chartbuster hit first recorded by The Ink Spots in 1940, and later by Glenn Miller, Pat Boone, and even, in an at-home private session, Elvis (they’re all on YouTube). I was reminded of the tune by recent reports of flamingos flocking back to Florida.

The flouncy fowl, averaging up to 5-feet tall with their long, lithe necks and stilt-like legs, were once so common here, and so beloved, that folks even adorned their lawns with life-size replicas. The once ubiquitous plastic birds were invented for Union Products in 1957 by artist Donald Featherstone (no pun intended!) and are still marketed today.

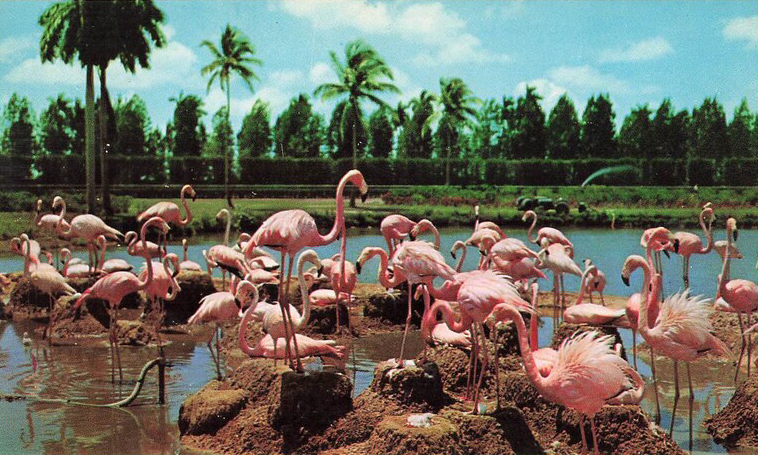

The highly social birds commonly congregate in colonies of hundreds or even thousands. They can live for 60 years or more and mate for life. Related to storks, ibises, and spoonbills, their black-tipped beaks are shaped to function, with their heads inverted, as scoops for sifting food from silt in shallow waters along the shore. Their feet are webbed for wading.

But perhaps the flamingo’s most distinctive feature, besides that lean and lanky look, is their reddish-pink color, which derives from their diet of shrimp, algae, and plankton. Their coloration led the ancient Greeks and Romans to name the lustrous creature phoenicopterus, “red-feathered.”

The species name “ruber” in the scientific name Phoenicopterus ruber also means “red,” as in RUBy/RUBella/RUBescent. English FLAMingo is a color-word too, deriving through Portuguese/Spanish from Latin flamma, meaning FLAMe. A flock of the flashy birds is commonly termed a FLAMboyance. Their chicks are called “chicklets” or “FLAMinglets.”

According to the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, the American or Caribbean flamingo is native to the state and once flourished in the Keys, the Everglades, and Florida Bay in great numbers. Fossil evidence from the Bone Valley Formation in Polk County confirms that the extinct species Phoenicopterus floridanus existed in central Florida from as early as the Pleistocene.

By the early 1900s, however, the flamingo had practically disappeared from the state due to overhunting for their meat and particularly for their handsome feathers, used to adorn hats and other FLAMboyant attire.

In the 1930s a flock was imported from Cuba to Hialeah, where they have been maintained ever since on the park’s infield lake, a National Audubon Sanctuary. The bird has appeared in the logo of the Florida state lottery from its inception in 1986 and been featured in numerous movies and TV shows, including the 1984-89 series “Miami Vice.”

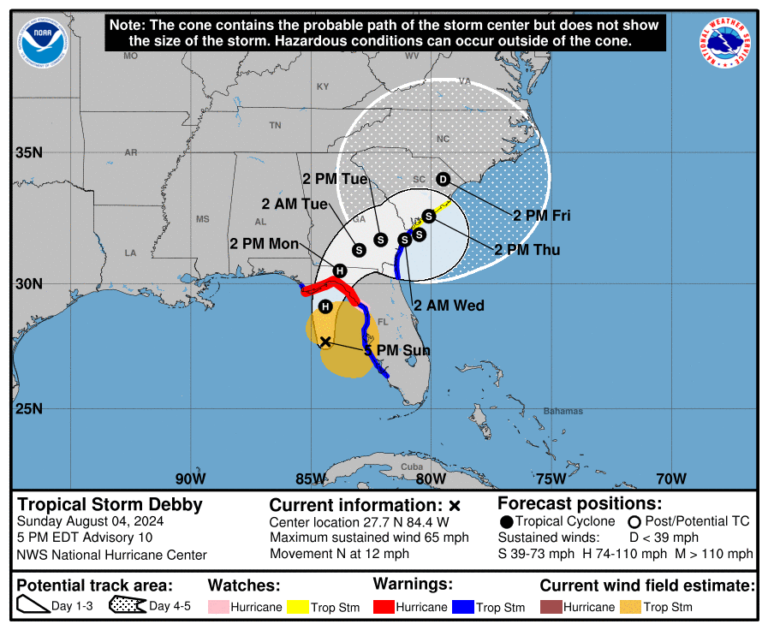

Otherwise, flamingos had been rarely seen in the wild here for decades until recently, in the aftermath of Hurricane Idalia. Winds from Idalia, which formed in the Caribbean this past August, drove a sizable number of the birds off their usual migration course into the Sunshine State.

The American Birding Association reported sightings in Wakulla, Alachua, Pinellas, and other Florida counties. One boat captain counted 17 in the surf and on the beach near St. Petersburg in September. The birds, who can fly upwards of 400 miles in a single day, were spotted even further north in the weeks following the storm, in Georgia, the Carolinas, Kentucky, and even Ohio and Wisconsin.

In ancient Rome, the bird was so admired for its speed and beauty that it was chosen symbol of the Russati, the “Reds,” one of the four chariot-racing teams in the Circus Maximus. In one comic mosaic scene flamingos are shown pulling race chariots themselves.

But flamingos were prized also as fine cuisine. The imperial cookbook of Apicius has recipes for boiling and for roasting the bird in egg sauce. The 2nd -century A.D. satirist Juvenal mentions a lavish banquet featuring an enormous flamingo.

A much sought-after delicacy was the bird’s tongue, a favorite of the 1st century emperor Vitellius. In an epigram from the same period by the poet Martial, a flamingo observes that, while it was named for its ruby-red plumage, what gluttons were after was its tongue; but, the bird threatens, “what if my tongue could tell tales?”

In the U.S. today, thankfully, flamingos are protected under the Federal Migratory Bird Treaty Act, so it’s illegal to kill or capture them or to eat them or their eggs (they typically lay only one a year). So, when National Pink Flamingo Day rolls round on June 23, we’ll admire the bird’s beauty and maybe even erect a statue on our lawn – but Alice rightly insists on a wooden one (you can find them at Walmart!) to spare the chicklets, and the planet, from pink plastic pollution.

Rick LaFleur is retired from 40 years of teaching Latin and Classics at the University of Georgia; his latest books are The Secret Lives of Words, a collection of his widely distributed newspaper columns, and Ubi Fera Sunt, a lively translation into classical Latin of Maurice Sendak’s children’s classic, Where the Wild Things Are. He and wife Alice live part of the year in Apalachicola, under the careful watch of their bobtail manx Augustus.

Meet the Editor

David Adlerstein, The Apalachicola Times’ digital editor, started with the news outlet in January 2002 as a reporter.

Prior to then, David Adlerstein began as a newspaperman with a small Boston weekly, after graduating magna cum laude from Brandeis University in Waltham, Massachusetts. He later edited the weekly Bellville Times, and as business reporter for the daily Marion Star, both not far from his hometown of Columbus, Ohio.

In 1995, he moved to South Florida, and worked as a business reporter and editor of Medical Business newspaper. In Jan. 2002, he began with the Apalachicola Times, first as reporter and later as editor, and in Oct. 2020, also began editing the Port St. Joe Star.